|

| Ernest Hemingway in the apartment on rue Notre-Dame-Des-Champs in 1924 |

Paris, undoubtedly, was the making of Ernest Hemingway. He lived in the French capital for only six years. When he arrived there with his wife Hadley in December 1921, he was an ardent, but rather uneducated, writer; by the time he left Paris with Pauline Pfeiffer (wife #2), in March 1928, he was a successful author, with three books under his belt - including his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, which was based partly on his experiences on the Left Bank of the French capital in the mid-1920s.

|

| Hemingway's U.S. passport issued in 1923 |

I first became aware of Hemingway's profound debt to Paris back in 2010, when my family and I made our first trip to Cuba Cuba Paris

|

| Front cover of his Paris memoir |

A Moveable Feast is a fascinating book. Hemingway worked on it for about two-and-a-half years in the late 1950s. It is very episodic - consisting of twenty chapters, most of which are concise in style and precise in their telling details. It may be a memoir, but he wrote it in a semi-fictional style - giving details and dialogue for events that had happened thirty-five years previously. In his brief Preface, he wrote: "This book may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a book of fiction may throw some light on what has been written as fact." It is, by turns, both a magnanimous and a very bitchy look at some of the key figures of that period in his life. He speaks glowingly of Sylvia Beach and Ezra Pound; he is more ambivalent about Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald; and he is quite vicious about Ford Madox Ford. You get the sense that he wanted to settle the score with some of these writers - people he had learned a lot from, after all, but with whom he felt always that he was in competition. He had always been insecure that way. More interesting, perhaps, than the dirt he throws at some of these well-known writer-friends of his is the account he gives of how he slowly worked on his writing style; learning both from the Russian and French masters he was reading voraciously and the one-on-one advice he was getting from his Left Bank colleagues - especially Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. And the vignettes create an atmospheric portrait of a city that was surely the centre of the artistic world at that time.

|

| Le Dome café on Boulevard Montparnasse in 1920 |

It was the reading of A Moveable Feast and my visit to Hemingway's Cuban home (documented in a previous blog post of mine - "Hemingway in Cuba - Ambos Mundos & Finca Vigia", February, 2012) which got me hooked on Hemingway. Within a year I had read three or four major biographies of the man and had begun collecting hardcover copies of his novels and short story-collections. So, when my wife and I decided about a year ago to visit Paris this past summer, I knew I had to re-read all the books I had which were focused on Hemingway's Paris years; and I had to plan out in detail all the important Hemingway sites on the Left Bank - so that I could visit and photograph them. What follows in this blog post are some of the photos from that visit of ours to Paris in July, 2013. And an historical account that puts the pictures into perspective.

|

| Sherwood Anderson persuaded Ernest and Hadley Hemingway to settle in Paris |

It was the American writer Sherwood Anderson who got Ernest Hemingway to Paris. After he left his parents' home in Oak Park, Hemingway moved to Chicago in October, 1920 and shared a place there with friends. He soon met Hadley Richardson, with whom he began a courtship - conducted primarily by daily exchanges of letters. Hemingway also fell in with the literary set in Chicago, and met fiction-writer Sherwood Anderson and poet Carl Sandburg. Anderson had only recently had his notable collection of inter-related short stories, Winesburg, Ohio (1919) published. Anderson was particularly helpful to Ernest, who was already an aspiring writer. As Hadley and Ernest began to talk and write about marriage, Hemingway shared with her his desire to leave America and set up residence in Italy. He wanted to show her the places he'd been during the war; and he yearned to establish the kind of lifestyle that would give him the time and space to work on his stories.

|

| Left-to-Right: Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Ezra Pound and John Quinn outside Pound's apartment in 1923 |

Anderson had his own travel plans; he was going to move to Paris - to join the large numbers of American expatriate writers and artists who had set themselves up in the French capital - reveling in the bohemian lifestyle there, and taking advantage of a very favourable exchange rate. Anderson encouraged the Hemingways to consider making the same move. Ernest had met Anderson in early January, 1921. The older writer (he was in his mid-forties) was a considerable influence on Hemingway: he advised the younger man to shift his attention from magazine-based popular fiction to literary work.

|

| 1920s café society in Paris |

But then Anderson was suddenly gone - three months after meeting Hemingway, he left Chicago for Paris. But he was back in Chicago in October. He told Ernest again, that if he really wanted to be a serious writer, Paris was the place to be - not Italy. There were so many great writers there, and he offered to give Hemingway letters of introduction to some of the key figures he had met there that summer - Sylvia Beach, Ezra Pound, Lewis Galantiere and Gertrude Stein.

|

| Hadley Richardson, Ernest's wife, in 1920 |

Hemingway hesitated. He had been dreaming of getting back to Italy for two years. But the set-up in Paris sounded enticing. Hadley would be able to get by in the language - she had studied French for eight years in school. She also had an annual income of $3,000 from several trust funds. And Hemingway could supplement that by writing freelance articles for John Bone, an editor at The Toronto Star who offered Ernest a job as a kind of roving reporter doing features for the paper. Hemingway would work out of the Star's Paris office; and Bone would pay regular space rates and reimburse all legitimate expenses. Hemingway thought about it. He could begin writing immediately in Europe - and get paid for it - whilst he set up the conditions required to focus his attention on fiction. So it was set. Paris it would be. On December 3rd. Anderson gave Hemingway several letters of introduction to present to the likes of Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. He also wrote to Lewis Galantiere asking him to help the young man settle in the French capital. Hemingway's association with Anderson had been brief, but intense. It was to be the model for many more relationships in the years ahead. He always seemed to be in the right place at the right time - making friends quickly, listening intently and learning, and then moving on.

|

| First night at the Hotel Jacob et L'Angleterre |

Ernest and Hadley Hemingway arrived in France at the port-city of Cherbourg on December 21st., 1921. They took a quick train to Paris. They stayed their first night in Paris in Room 14 at the Hotel Jacob et L'Angleterre, a hotel on the Left Bank (the south-side of the River Seine) in the St-Germain area - just west of the Latin Quarter. Sherwood Anderson had stayed there the previous fall. James Joyce had been a resident, too. It was a popular destination for English-speaking writers and artists in the 20s. Among the other well-known visitors: Washington Irving, Gertrude Stein, Lewis Galantiere, and Djuna Barnes. The hotel, now called Hotel D'Angleterre is at 44 rue Jacob in the 6th. arrondissement. It is found near the corner of rue Bonaparte and rue Jacob. The Hemingways stayed here for two weeks until they found their first apartment in early January, 1922. Nearby is the impressive romanesque church of St-Germain des Prés.

|

| Les Deux Magots café at the corner of Boulevard Saint Germain and rue Bonaparte |

It didn't take long for Ernest and Hadley to discover the delights of French cuisine and the amiable ambience of Parisian cafés and restaurants. Just a five-minute walk east of their hotel, Hemingway soon discovered the café Le Pré aux Clercs at 30 rue Bonaparte. It was moderately-priced and became one of their favourite haunts in those early days. Ten minutes west of the hotel, at 29 rue des Saints-Pères, was the considerably more expensive Michaud's. It was beyond what they could generally afford, but they would dine their occasionally as a treat. James Joyce and family were often there - thanks to the support he continued to receive from several wealthy patrons (most notably Harriet Weaver).

|

| Café de Flore - obligatory and, hence, expensive tourist stop on Boulevard Saint Germain |

For breakfast or lunch, or a late-afternoon cocktail before dinner, the Hemingways could stroll south a couple of blocks on rue Bonaparte to the Boulevard Saint Germain and try to find a table at two very-popular cafés: the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots. These spots became even more renowned after WWII as the favourite hang-outs of left-wing intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre and his partner Simone de Beauvoir.

|

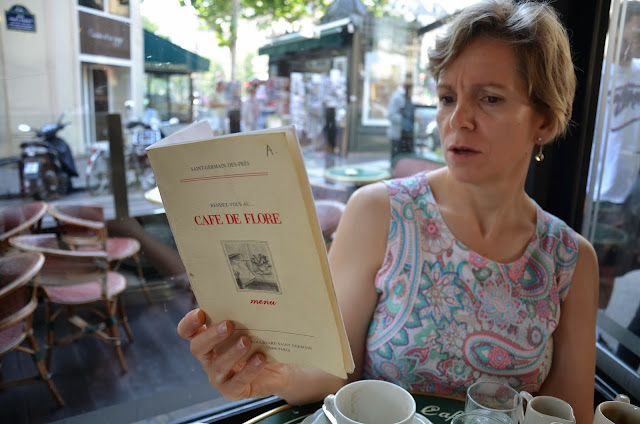

| Breakfast at the Cafe de Flore: Barbara ponders the outrageous price of a cup of coffee |

Barb and I had breakfast at the Café de Flore: a couple of coffees and a pastry each. The waiters - and there were lots of them - were dressed up in the traditional black-and-white uniforms: black waistcoats and dickey bow ties, and a large, white, linen napkin draped over their left forearm. The elegant service almost seemed to justify the exorbitant cost of this meagre fare - but not quite!

|

| Breakfast croissants at the café de Flore |

In Hemingway's time there were some expensive spots to eat and drink on the Left Bank, but generally it was a cheap area of the city - which is why the usually impoverished artists and writers would congregate there. Only five weeks after arriving in Paris, Hemingway wrote an article for The Toronto Star Weekly explaining how cheap it was to live in the city. His article was called "Living on $1,000 a Year in Paris" (February 4th., 1922). "Paris in the winter," he wrote, "is rainy, cold, beautiful and cheap. It is also noisy, jostling, crowded and cheap. It is anything you want - and cheap." He went on to explain the significance of the exchange rate; as he summarized, "Exchange is a wonderful thing." Some of his interesting details: "Breakfast costs us two francs and a half (about 25 cents)." He and Hadley could eat a four-course meal at a "splendid restaurant" [he was probably referring to Le Pré aux Clercs] for about 50 cents. Avoid the touristy spots on the Right Bank, he recommended; life in the Latin Quarter was incredibly cheap.

|

| Top of the hill: 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine - Hemingway's first apartment (entry is the blue door) |

After about ten days in Paris at their hotel, the Hemingways began to look for an apartment to rent in early January. Pretty quickly they found a place on rue du Cardinal Lemoine, at the eastern edge of the Latin Quarter. They signed the lease on January 7th., 1922. Hemingway had read in The Tribune (an English-language newspaper published in Paris) that a furnished apartment ought to be available in the city for 1,000 francs per month (about $85). So he was delighted with himself when he found a place for only 250 francs per month (about $20).

The apartment was a third-floor walk-up located at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine. It was not, truth be told, a very salubrious neighbourhood. Some of their friends were surprised to find them in such a run-down, working-class area; but Hemingway liked to think of it as an interesting and unpretentious spot - a very old part of the city with lots of character. The apartment had just two small rooms and a tiny kitchen. The Hemingways hired a femme du ménage: she would cook breakfast for them, clean up and empty the bed pan (the apartment had no toilet). She would return in the late afternoon to prepare an evening meal.

|

| 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine |

|

| Plaque outside 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine |

"Home in the rue Cardinal Lemoine," Hemingway recalled in A Moveable Feast, "was a two-room flat that had no hot water and no inside toilet facilities except an antiseptic container, not uncomfortable to anyone who was used to a Michigan outhouse. With a fine view and a good mattress and springs for a comfortable bed on the floor, and pictures we liked on the walls, it was a cheerful, gay flat."

To his family back in Oak Park, Michigan, Hemingway described the apartment in a letter he wrote in late-January, 1922: "[It] is the jolliest place you ever saw ... It is the most comfortable and cheapest way to live and Bones [Hadley] has a piano and we have all our pictures up on the walls and an open fire place and a peach of a kitchen and a dining room and big bed room and dressing room and plenty of space. It is on top of a high hill and in the very oldest part of Paris. The nicest part of the Latin quarter. Just back of the Pantheon and the École Polytechnique. It has a tennis court right across the street and a bus line ends in the square just around the corner so that you can get anywhere in the city."

|

| Our hotel at the corner of rue du Cardinal Lemoine and rue des Ecoles - the Hotel Royal Cardinal |

In the early stages of our planning for this trip to Paris, I already had a preliminary list of Hemingway sites that I knew I just had to visit. Several of them were tucked in and around the rue Cardinal Lemoine. So it was quite a surprise to discover that my wife's research about hotels that we might stay at in the Latin Quarter had narrowed the choices down to a few, and that one of them - the Hôtel Royal Cardinal - was at the corner of rue du Cardinal Lemoine and rue des Écoles. I checked my detailed Michelin map of Paris. It was only a ten-minute walk up the hill - a very steep hill, it turned out - to Hemingway's apartment. It was the hotel we booked.

|

| L'accordeoniste at a bal musette |

Underneath the Hemingways' apartment, on the ground floor of the building at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine, they discovered, was a bal musette. This was a type of dance hall established in Paris in the late nineteenth-century by a wave of immigrants into Paris from the Auvergne. Many of these Auvergnats opened cafés and bars, which served as small dance halls in the evenings. In the early days, customers would dance to the music of the cabrette (a kind of bagpipe known in Paris as the "musette") and the vielle a roue (the hurdy-gurdy). Eventually the accordion became a dominant instrument in these establishments - although the music was usually provided by a small combo of instrumentalists. The dance hall below the Hemingways' apartment was called Bal au printemps.

|

| Ford Madox Ford - Hemingway found him very annoying |

In the section of A Moveable Feast called "Ford Madox Ford and the Devil's Disciple", where Hemingway paints a very unflattering portrait of the English author, Ford goes on about an interesting little bal musette that he has discovered near the Place Contrescarpe on rue du Cardinal Lemoine. He keeps inviting Hemingway to join him and a few friends there - oblivious to the fact, as Hemingway keeps telling him, that he had lived above the place for two years. "How odd," Ford remarks, "are you sure?" Hemingway sets a scene in this dance hall in Chapter III of his first novel, The Sun Also Rises. "Five nights a week," he writes, "the people of the Pantheon quarter danced there. One night a week it was the dancing-club. On Monday nights it was closed. When we arrived it was quite empty, except for a policeman sitting near the door, the wife of the proprietor back of the zinc bar, and the proprietor himself."

|

| Hemingway's Toronto Star I.D. card |

Once Ernest and Hadley were ensconced at no. 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine, Hemingway threw himself into his work for the Toronto Star. He would have preferred, of course, to focus exclusively on writing short stories, but he wanted to bring in as much income as he could, in order to fund their travels to Switzerland, Italy and Spain. He worked diligently on his journalism: in his first two months in Europe, Hemingway sent 30 feature stories to John Bone in Toronto. But he often found it difficult to concentrate on his writing during that first winter of 1922. He must have recalled the advice that Sherwood Anderson had given him back in Chicago - that a writer ought to have a separate place to write in, so that he could be free of any disturbances. He decided to do just that - renting a small room in the attic of a building just around the corner on rue Descartes. The house - at 39 rue Descartes - had previously been a hotel. The French poet Paul Verlaine had died there in January, 1896. Hemingway described the scene there in the second chapter of A Moveable Feast:

|

| 39 rue Descartes - once a hotel where poet Paul Verlaine died |

On our second evening in Paris, Barbara and I strolled around the area just south of our hotel in search of a restaurant. We went up rue du Cardinal Lemoine - stopping briefly at no. 74, where Barb took a picture of me outside the front door of the Hemingway apartment. Then we continued south - going downhill now - towards the Place Contrescarpe (mentioned in the very first paragraph of A Moveable Feast). And further on, past the attractive square, to explore a great variety of eating spots down on rue Mouffetard. This narrow street hosts an outdoor market four days a week, as it did back in Hemingway's time; he and Hadley would shop there regularly.

And then we retraced our steps back up Mouffetard and, when we reached Place Contrescarpe, we went left up rue Descartes, instead of going back to Cardinal Lemoine. We found a small restaurant on rue Descartes with an attractive patio - about a dozen small tables set out on the cobblestoned street. We studied the menu posted outside. It was a prix fixe restaurant. For 18 euros (about $18.00), you could get a starter and an entrée, or an entrée and a dessert. A good deal. We dined there - adding to the food a large carafe of the house wine. It was a fine meal - our enjoyment increased by a jazz guitarist busking across the street for twenty minutes and by the constant parade of interesting people passing by.

|

| Hemingway didn't live here; he wrote in an attic room (1922-23) |

|

| Café Delmas in Place de la Contrescarpe |

Leading further south and downhill out of the square was the rue Mouffetard - "that wonderful narrow crowded market street" as Hemingway described it. There was an open air marché (market) there on most days of the week. Ernest and Hadley would meander down the narrow lane and purchase things to take home for their cook to prepare.

Rue Mouffetard ("La Mouffe", as it's called by the locals) still hosts a bustling market - it operates from 8 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., Tuesday to Saturday; and from 8 a.m. to noon on Sunday. Even without the outdoor stalls, the street is a shopper's delight: there are some interesting specialty shops - like the Androuet fromagerie (cheese shop) and a couple of stores offering fine wines from all over France. And all the way down, from Place Contrescarpe to the St. Médard square, there is a wide variety of restaurants and fast-food establishments. I even found a good book shop - L'Arbre du Voyageur - at the corner of rue Ortolan - just a couple of blocks down from Contrescarpe. I went in and bought French versions of For Whom the Bell Tolls ("Pour qui sonne le glas") and The Sun Also Rises ("Le soleil se lève aussi").

Ernest and Hadley had only been in Paris for about a week when Hemingway used the first of the letters of introduction that Sherwood Anderson had penned on his behalf. It was addressed to Sylvia Beach, an American woman who ran an influential English-language bookshop on the Left Bank called Shakespeare and Company. Her bookstore had originally been located at 8 rue Dupuytron, but in May, 1921, Beach moved it to 12 rue de l'Odéon, about half-way between the Boulevard Saint Germain and the Luxembourg Gardens.

Sylvia Beach took an immediate liking to this young and aspiring writer, who - by turns - could be charming and insecure, or brash and rather too sure of himself. But Beach was a friend, mentor and supporter of many of the key literary figures of the day living in and around the Latin Quarter.

Just a couple of months after her first meeting with Hemingway, for example, Beach received her first shipment of James Joyce's Ulysses. She had published the modernist classic herself, after many other publishers had rejected the book, because of their fear of being prosecuted.

|

| Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in 1920 - she was the first publisher of Ulysses, which Joyce finished in an apartment on rue du Cardinal Lemoine |

Just a couple of months after her first meeting with Hemingway, for example, Beach received her first shipment of James Joyce's Ulysses. She had published the modernist classic herself, after many other publishers had rejected the book, because of their fear of being prosecuted.

Sylvia Beach gets her own chapter in A Moveable Feast: "No one that I ever knew," Hemingway wrote, "was nicer to me." Beach was 12 years older than him - in her mid-thirties. "Sylvia had a lively, sharply sculptured face," he continued, "brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal's and as gay as a young girl's, and wavy brown hair that was brushed back from her fine forehead and cut thick below her ear and at the line of the collar of the brown velvet jacket she wore. She had pretty legs and she was kind, cheerful and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip."

|

| Hemingway inside Shakespeare and Company in early 1922 |

Hemingway's main ambition was to write short stories - not popular yarns for the glossy magazines any more, but literary stories. His models were no longer Ring Lardner and H.G. Wells; now he was carefully reading and studying James Joyce and Ivan Turgenev. Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and other luminaries, were regular visitors to Shakespeare and Company. Beach became an important early supporter of Hemingway and she helped to integrate him into this colony of British and American expatriate writers.

Soon after setting themselves up in their new apartment on rue du Cardinal Lemoine, the Hemingways escaped the miserable winter weather in Paris by journeying south-east to the Swiss Alps. Friends they had made on their trans-Atlantic boat trip, and whom they met again at the Hotel Jacob, had recommended an inexpensive pension in Switzerland at Chamby sur Montruex. It was perched a thousand feet above Lake Geneva. They got there from Paris after a twelve-hour train trip. It was a three-week skiing holiday. They left Paris on January 10, and were back on February 2nd.

|

| A photograph of Ezra Pound by Man Ray (1923) |

In some ways, Hemingway was guilty of projection. He often criticized in scathing terms things that he feared and disliked about himself. In those early days in Paris he must have been terribly insecure and unsure of himself. He probably felt very uneducated and inexperienced in the presence of some of these impressive thinkers and visionaries. He was still ambivalent about the notion of being a serious writer. It clashed with that other sense of himself as a man of action. As his career developed, Hemingway emphasized the latter image as a way of deflecting the public's attention away from his need to establish an authentic self-image as a devoted author.

In the brief course of his relationship with Ezra Pound (six months in Paris, and two months in Italy), however, Hemingway came to respect the older writer's generosity of spirit and his keen eye for good writing. Pound gave Hemingway lots of sound advice about how to write strong and lucid prose - stripped of flowery adjectives and flabby adverbial qualifications. "Go in fear of abstractions," Pound advised. Symbols must emerge naturally out of the details of a story, not be imposed from outside. Hemingway, as usual, was lucky to be in the right place at the right time; Ezra Pound soon left Paris for Italy. In fact he moved permanently to Rapallo, in north-west Italy, in 1924. Pound lived in the Montparnasse area of the Left Bank on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs - a street that Ernest would move to later.

|

| Man Ray's famous photo of Gertrude Stein (right) and Alice B. Toklas at 27 rue de Fleurus |

And then in early March, 1922 Hemingway had his first encounter with the American writer and art-collector Gertrude Stein - yet another contact made through an Anderson letter. As with Sylvia Beach and Ezra Pound, Stein has happy to serve as mentor for an ardent and serious young writer. Hemingway would walk from his home on the eastern edge of the Latin Quarter, past the Pantheon - with its basement crypts full of famous French authors and intellectuals, and take a pleasant short-cut through the Luxembourg Gardens - one of the city's finest parks. Gertrude Stein lived at 27 rue de Fleurus - just west of the Gardens, near the corner of the Boulevard Raspail and rue de Vaugirard - with her long-time companion Alice B. Toklas. Gertrude and her brother Leo had first established themselves in the spacious apartment on rue de Fleurus in 1903. Leo had stayed until 1914, and the siblings had amassed an impressive collection of modern French art - works they had acquired from the many Paris-based artists who frequented their evening salons. When Leo Stein relocated to Italy in 1914, they divided the collection.

When Hemingway visited Gertrude Stein at her apartment, he found her sitting in a large room made out as a big studio: "It was like one of the best rooms in the finest museum," he recalled in A Moveable Feast, "except there was a big fireplace and it was warm and comfortable and they gave you good things to eat and tea and natural distilled liqueurs made from purple plums, yellow plums or wild raspberries ... Miss Stein was very big but not tall and was heavily built like a peasant woman. She had beautiful eyes and a strong German-Jewish face that also could have been Friulano and she reminded me of a northern Italian peasant woman with her clothes, her mobile face and her lovely, thick, alive immigrant hair which she wore put up in the same way she had probably worn it in college. She talked all the time and at first it was about people and places."

|

| Front entrance to Gertrude Stein's apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus |

Miss Stein - as Hemingway called her - was surrounded by works of Picasso, Matisse, Braque and Cézanne. She tutored him in her deep knowledge of modern art, encouraging him to visit the many masterworks in the palace at Luxembourg Gardens - the Musée du Luxembourg - which he often did.

But, more importantly, she gave him advice on writing. She was a keen writer herself, an unusual and idiosyncratic stylist. She reinforced Ezra Pound's view about the importance of a simple, direct approach. She also emphasized the importance of rhythm, and showed Hemingway how the repetition of key words and phrases could be used as both a thematic and a rhythmic device.

But, more importantly, she gave him advice on writing. She was a keen writer herself, an unusual and idiosyncratic stylist. She reinforced Ezra Pound's view about the importance of a simple, direct approach. She also emphasized the importance of rhythm, and showed Hemingway how the repetition of key words and phrases could be used as both a thematic and a rhythmic device.

|

| Gertrude Stein (godmother) with Jack ("Bumby") in Luxembourg Gardens |

In August, 1923 the Hemingways left Paris for Toronto. Hadley was pregnant, and they both agreed to come back to north America for the birth of their child. John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway - nicknamed "Bumby" - was born at the Wellesley Hospital in Toronto on October 10th. Hemingway had been working full-time for The Toronto Star since their return, and the experience - under the stern and unsympathetic leadership of Harry Hindmarsh - was very disagreeable. They had had no definite plans about how long they'd stay in north America, but the horrible weather and the dissatisfying work situation pushed them back to Paris earlier than they might have expected. Three months after their son's birth they were on a boat back to Paris.

|

| Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs |

The French capital seemed even more inundated with expatriate Americans. When the Hemingways first arrived in Paris in December 1921, there were about 6,000 Americans. By now there were about 32,000 permanent American residents in the city, taking advantage of the very favourable exchange rate - not to mention about 60,000 British residents. Ernest and Hadley moved briefly into a hotel.

But within a week they had found an apartment to lease on Ezra Pound's street - at 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, just north of the Boulevard Montparnasse. They would be paying 650 Francs per month (about $30.00) - three times the amount they had been paying for the place on rue du Cardinal Lemoine.

But this was a much better place - more spacious, in a more salubrious neighbourhood, and closer to their friends. Later on, Ford Madox Ford and his partner, Stella Bowen, moved into a flat on the street - in between the Hemingways and Ezra Pound. The Hemingways were just a few minutes away from the Port Royal train station, the Vavin metro stop, Stein's apartment, Beach's bookshop, and the Luxembourg Gardens - which became a regular destination, now that they had an infant. But there was still no gas and no electricity. And in the courtyard below, during the day, there was the constant buzz of an electric saw in a small lumberyard. To make their domestic life easier - and to help care for little Bumby - they hired again Marie Rohrbach, the femme du ménage who had worked for them back on Cardinal Lemoine. They had the whole of the second storey at 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs.

|

| Hemingway outside the apartment on Notre-Dame-des-Champs in 1924 |

But within a week they had found an apartment to lease on Ezra Pound's street - at 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, just north of the Boulevard Montparnasse. They would be paying 650 Francs per month (about $30.00) - three times the amount they had been paying for the place on rue du Cardinal Lemoine.

|

| Hemingway's apartment building at 113 Notre-Dame-des-Champs |

Hadley described the set-up in a letter (February 20, 1924) to Grace Hemingway, her mother-in-law: "We have a tiny kitchen, small dining room, toilet, small bedroom, medium sitting room with stove, dining room where John Hadley sleeps and the linen and his and our bath things are kept, and a very comfortable bedroom ... you're conscious all the time from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. of a very gentle buzzing noise [below]. They make door and window frames and picture frames. The yard is full of dogs and workmen, and rammed right up against the funny front door covered with tarpaulin is the baby's buggy."

Their apartment was also just a brief stroll away from the hub of Left Bank café society on Boulevard Montparnasse: La Rotonde and Le Dôme, opposite each other on the north and south side respectively of the Boulevard - at the corner of the Boulevard Raspail - and Le Select, one block west of La Rotonde.

And around the corner from Le Dôme, at 10 rue Delambre was the Dingo American Bar, where Hemingway says in A Moveable Feast that he first met F. Scott Fitzgerald and Duff Twysden. Twysden would become the model for Brett Ashley, Jake Barnes's love-interest in Hemingway's first novel, The Sun Also Rises.

The first eight chapters of that book are set primarily in the Montparnasse area, with its disaffected cast of expatriate characters seemingly going around in circles and returning obsessively to Le Select.

|

| La Rotonde café at corner of Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard Montparnasse |

And around the corner from Le Dôme, at 10 rue Delambre was the Dingo American Bar, where Hemingway says in A Moveable Feast that he first met F. Scott Fitzgerald and Duff Twysden. Twysden would become the model for Brett Ashley, Jake Barnes's love-interest in Hemingway's first novel, The Sun Also Rises.

|

| Le Dome - across the street from La Rotonde - the Dingo Bar was just round the corner |

The first eight chapters of that book are set primarily in the Montparnasse area, with its disaffected cast of expatriate characters seemingly going around in circles and returning obsessively to Le Select.

|

| Le Select café - a hub for action in The Sun Also Rises |

|

| Looking down on Montparnasse from the fifty-floor Tour Montparnasse: you can see the red awning of La Rotonde cafe at centre-right; the Luxembourg Gardens near the top of the photo |

Even closer to Hemingway's apartment on rue des Notre-Dame-des-Champs was the cafe La Closerie des Lilas. It was located directly south of the Luxembourg Gardens at the corner of the "Boul' Mich" (Boulevard Saint-Michel) and Boulevard Montparnasse. It quickly became Hemingway's favourite haunt - it was the closest to home, and it wasn't as popular with the bohemian poseurs rampant just down the street at the likes of Le Select and La Rotonde. "There was no one there they knew," Ernest wrote in A Moveable Feast, "and no one would have stared at them if they came. In those days many people went to the cafes ... to be seen publicly and in a way such places anticipated the columnists as the daily substitutes for immortality."

Depending on the weather, and whether or not he was busy working on a short story, Ernest would sit either outside on the patio, or inside at a favourite table near the back of the place. Out on the patio he would sit with his back to the café so he could gaze across at the statue of Marshal Ney that sat at the corner of the two famous boulevards. He recalls the fascination he had for that statue in his memoir: "I thought that all generations were lost by something and always had been [an allusion probably to the Gertrude Stein epigram he puts at the beginning of The Sun Also Rises - "You are all a lost generation"] and always would be and I stopped at the Lilas to keep the statue company and drank a cold beer before going home to the flat over the sawmill."

I wanted to have lunch with Barbara at La Closerie des Lilas, and sit near where Hemingway would have spent hours working on his short stories. But when we got there, I was alienated by the prices posted on the menu outside: salads for $20; entrees averaging about $35. It had became a very upscale destination. And the patio, where Ernest could gaze across the sidewalk to the Statue of Marshall Ney, was hidden behind a tall screen of potted cedar bushes. It was all boxed in and hidden. Disappointed, I found a more modest café just across the street.

|

| Barbara and I have lunch on Boulevard Montparnasse (at the corner of Boulevard Saint Michel) |

After he was settled into the apartment on rue Notre-Dame-des- Champs, Hemingway began frequenting La Closerie des Lilas regularly for refreshments and a quiet place to write in a back corner. He suddenly hit a hot streak. The short stories begun to flow from his pencil like never before. He was astonished. In the space of about three months, he wrote eight of his best, early short stories. It had all come together. Everything that he had long been reaching for, everything that he had learned in the past two years, was to hand. He finally sensed a mastery of the form that he had been struggling with for so long. And in just a couple of years he would be working on his first novel, set along these Left Bank boulevards, and featuring the sort of American and British expatriates that he had once sneered at, but now found himself in some sympathy with - The Lost Generation.

In many ways he had found a home in this place and amongst these people. There was something exceptional about the whole experience. To his mother Grace, on February 14th., 1922, he wrote: "It is fun living in this oldest quarter of Paris, and we have a wonderful time. Paris is so very beautiful that it satisfies something in you that is always hungry in America." It was sophisticated, enlightening, tolerant, and exciting.

"If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man," Hemingway said to a friend in 1950, "then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast."

And he sums up the effect in his memoir's final paragraph: "There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached. Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you brought to it. But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy."

If you, too, plan to get to Paris, read A Moveable Feast, and read The Sun Also Rises. Stroll around the Latin Quarter and Montparnasse. Soak up the atmosphere. And marvel at the incredible scene it must have been there when Hemingway was around in the 1920s.

|

| "... wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast." |

Photographs

© Clive W. Baugh

(using

a Nikon D7000 with a Nikkor 18-105 mm zoom lens)

Resources:

A Moveable Feast (1964) by Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926) by Ernest Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway on Paris (2010) selected articles by Hemingway from The Toronto Star (1920-1924) published by Hesperus Press, The Young Hemingway (1986) by Michael Reynolds, Hemingway: The Paris Years (1989) by Michael Reynolds, The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: 1907-1922 (2011) edited by Sandra Spanier & Robert W. Trogdon, Bloom's Literary Guide to Paris (2007) by Mike Gerrard.

Good one Clive. I love Barbara's look of horror at the prices on the menu!!!!

ReplyDeleteYou have described Hemingway's sojourn in Paris succinctly. Marilyn and I have been to Paris many times over the years and we have seen some of these places and probably passed others unknowingly. I must doa Hemminway tour paris now..

I'd like to include Oscar Wilde and perhaps George Orwell into the mix. Could end up staying in Paris forever!!!

Tony

Hi Clive, we met at a book signing at Chapters Ancaster, thanks again for buying my book, I hope you enjoy it!

ReplyDeleteI took your advice and read A Moveable Feast...and loved it! I can see how you got hooked after reading this. I have read some of his other works, but I plan to read more of them now.