|

| Charles Dickens in 1869 |

There was a four-year gap between the conclusion of Our Mutual Friend (August 1865) – Charles Dickens’s final completed novel – and the time when he began contemplating a new novel in the summer of 1869. He no longer relied on his novels as a primary source of income: he was still editing his weekly magazine All the Year Round; he was collecting royalties from editions of his previous books; and he was earning substantial revenues doing public readings from his vast repertoire of fiction – novels and short stories. These performances had begun as one-off events, or limited runs, done to raise funds for Dickens’s favourite charities. But eventually he realised that they had the potential to become his main source of income. From here on in, Dickens devoted most of his professional time and effort to public readings. The effects were wonderful for his bank account, but disastrous to his health.

In January, 1866, Dickens decided to undertake a public reading tour of England and Scotland. His friends advised him against it. He wasn’t in good physical condition: he had suffered a mild stroke back in September; and he had a chronic problem with vascular degeneration which led to gout in his left foot. He had always been a keen walker – hiking, on average, about twelve miles a day when he was fit. He still continued to take long walks when he could manage it, but as his physical condition deteriorated, these excursions became impossible. He took to using a walking stick. And in the last couple of years of his life, he was often stuck indoors because of the pain of his swollen left-foot, and he needed physical support getting around. But he pushed himself to do this tour: he needed to work; he wanted the money; and he basked in the adulation of his audiences.

The tour began in late March, 1866 and ran into late June. His contract with Chappell and Company – whom he hired to handle all of the arrangements – specified a run of 30 public readings, for which he would be paid £1,500, plus extra to cover his personal and travelling expenses. This was Dickens’s first extended tour for four years. He was a meticulous man – so he prepared himself thoroughly. He had decided to add a new reading to his repertoire – the Christmas story about Cheap Jack that he had written the previous year. Once he’d prepared a reading script of the story, he rehearsed it to himself about 200 times! And then he did a private performance in front of friends – timing it to the second.

|

| Dickens doing a public reading in the U.S. in 1868 - an engraving from a sketch by Charles Barry |

Every aspect of the performances was planned with care. In his biography, Peter Ackroyd describes a typical stop on the tour. When Dickens first arrived in the city or town, he would immediately visit the venue, in order to do a ‘sound check’ and “take his bearings”: to check out the acoustics, and to monitor the seating arrangements. Occasionally – if he was not satisfied – he would insist on moving to another hall. They would set up a large, maroon screen on the stage behind him – seven feet high and fifteen feet wide. It served not only as a dramatic backdrop, but also as a device to project his voice more effectively out into the audience. His reading desk was set stage centre on a maroon carpet. At the front of the stage, on either side of Dickens, they set up gas-fired lamps that were fed by pipes. The lamps illuminated the prompt-copies for that day’s readings, and helped to set him up in a more dramatic fashion.

Dickens always wore evening clothes for his public readings. He would place a flower – usually a rose, or a geranium – in his buttonhole. And he would have his gold watch-chain hanging across the front of his waistcoat. The performances usually ran for two hours. The first reading – invariably a dramatic one – would go for ninety minutes. After a brief interval, Dickens would be back to do a second reading for about half an hour – usually a comic piece.

|

| Charles Dickens photographed in 1869 |

Dickens’s reading style, Peter Ackroyd points out, was affected by his acting technique. On stage, when he had been involved in amateur theatricals, he had always approached his roles seriously – he was never a ‘ham’. Despite his familiarity with the melodramatic style of his period, Dickens adopted a restrained manner – avoiding grand gestures, and building a character on the accumulation of small, incisive details. When he did his readings, he would use a sober approach – controlling carefully every rehearsed look and accent, in order to build up to the effect he was after. For these performances, Dickens was a reader, not an actor – he eschewed melodramatic mannerisms, and aimed for a realistic style that avoided cheap affectations.

This tour had a noticeable effect on Dickens’s health, but he persisted; and – even before the run was over – he opened negotiations with Chappell and Company to do another tour the following winter. They were happy to oblige. The gross receipts for the tour just completed was some £5,000 – they had paid Dickens £1,500, plus expenses. The winter tour was even more ambitious – a total of 42 nights. Dickens would get £60 per night (an increase of 20%), plus the usual extra for his personal expenses. It ran from January to May, 1867.

|

| 1866 editions |

In the summer of 1866, Dickens was busy again with literary matters. He was involved with the publication of a brand-new set of his novels – the Charles Dickens Edition. Once a month, one of his novels would be released in a single volume, priced at 3/6. The novels would be freshly set. Dickens would write a Preface for each. And – surely there were assistants for this task? – there would be a descriptive headline at the top of each right-hand page, itemising what was happening on those two pages of the novel. [This device is featured in the Everyman Editions of the novels which I have used throughout this series of blog posts.] This Charles Dickens Edition of 1866 was the most popular release of his books during his lifetime – actually it’s the first complete edition of his novels (except for the incomplete Edwin Drood, still yet to be written).

Despite the increasing damage to his health from the reading tour running from January to May of 1867, Dickens decided – again before the current one was complete – to undertake a gruelling tour of public readings in the United States. It was now 25 years since his first visit, and he had been receiving constant invitations to go over there for a tour. He did it for the money – he believed he could make a “fortune”. He was now supporting three main establishments: the family home at Gad’s Hill in Kent; the London home of his wife, Catherine, from whom he was separated; and the home he had recently set up on Linden Grove in Peckham for his lover, Ellen Ternan, and her mother. On top of that was the office space on Wellington Street in London he rented for his magazine and the temporary lodgings he often rented in the capital, in order to receive family and friends. And then there was the extended financial support or one-time gifts he provided to various family members and friends who were having money problems.

His closest friend and confidant, John Forster, had always advised Dickens against doing these public reading tours. He thought they were bad for his art – because they distracted him from his fiction and focused his effort primarily on pleasing his public – and damaging to his health. Dickens always ignored his friend’s protestations.

|

| Photo by J. Gurney in New York (1867) |

Dickens left for the U.S. on November 9, 1867. His first reading was in Boston on 2 December. He toured primarily around the north-east. In addition to his chronic health conditions, Dickens suffered through the entire trip with various colds. Regardless of how run down he was physically, he always rallied once he hit the stage. And the adrenalin seemed to revive him after each performance. But this was getting harder to do. He was constantly exhausted and depressed. Before going over to North America, Dickens had attempted to arrange things discreetly so that Ellen Ternan could accompany him. All his efforts came to nothing, however; he was terribly lonely without her. Things were so bad, Dickens decided to cut short his tour by a month; he cancelled visits to Chicago, the west coast, and Canada. Unbelievably, in the midst of all this physical and mental strain in the United States, Dickens negotiated with Chappell and Company to do yet another series of public readings in Britain – a “farewell tour”. Chappell suggested an incredible run of 75 performances. Dickens’s response? Let’s do 100. They agreed to pay him £8,000.

For this final series of public readings Dickens wanted to do something special. He decided to revive the excerpt from Oliver Twist that he had prepared some five years previously – the brutal murder of Nancy by Bill Sykes. He had abandoned the piece back then – thinking it was just too intense, too horrific, for a general audience. But now he was looking for something really dramatic – something sensational. The tour began on 6 October, 1868, but Dickens didn’t debut the “Sikes and Nancy” reading until 5 January, 1869 at St. James Hall. He put everything he had into the performance, and at its conclusion he was “utterly prostrate”. Almost as soon as this tour had begun, Dickens began to suffer a litany of problems – mental and physical. He continued to experience his chronic health problems. On top of that were mental distress, depression, and sleeplessness. And yet he continued to put himself through the emotional and physical exhaustion he suffered after each and every performance of “Sikes and Nancy”. His son, Charley, thought that it was the endlessly repeated murder from Oliver Twist that finally killed him. Others might not have accepted that it was that particular reading, but they agreed that the physical debilitation he experienced from this long series of tours must have accelerated his demise. Eventually, his doctors ordered him to cut short this tour.

|

| Rosa Bud sings; John Jasper plays - illustration from the original issue by Samuel Luke Fildes |

Dickens made a retreat back to Gad’s Hill Place and took it easy – at least for a while! The revival of his health and spirit prompted him to plan a new novel in the summer of 1869. He just could not stop working for long. The first idea he had come up with was that of a betrothed couple who do not marry until the very end of the book. Then he had something much better. He mentioned to his friend John Forster this “very curious and new” idea – the murder of a young man by his uncle, which is not revealed until the murderer reflects on his crime in his prison cell. He also planned to use opium as an exotic and intriguing element in the story – its consciousness-altering effects would be used as the agent of revelation. Dickens had recently visited an opium den in London – Bluegate Fields in the Limehouse area – with his visiting American publisher James Fields.

Once Dickens had a basic plot in mind, he approached his publishers, Chapman and Hall, in order to negotiate a contract. He proposed writing twelve monthly parts, instead of the traditional twenty. He knew now that much of his energy was gone, and that a sustained year-and-a-half campaign of writing was probably beyond him. He also advised Chapman and Hall to include a clause in the contract outlining how the publishers would recoup some of their outlay, if the author was unable to finish the novel because of death or incapacity. In return for the copyright, Dickens was to receive £7,500 and a half-share of the book’s profits. Dickens began work on the novel in the early autumn of 1869. He worked in two main locations: the Swiss chalet set up in his garden at Gad’s Hill Place; or the villa he had set up for the Ternans at Peckham in south-east London.

|

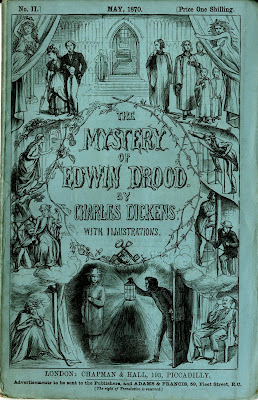

| Cover wrapper |

The first monthly issue of The Mystery of Edwin Drood was published by Chapman and Hall at the beginning of April, 1870. It sold about 50,000 copies. Each instalment would cost one shilling. The original plan would have seen the twelfth and final issue released in March 1871. As it turned out, only half the book was completed – the final section (Chapters 21-23) was issued posthumously in September, 1870 – three months after the author’s death. Dickens had originally planned to have his son-in-law Charles Collins – married to his daughter Kate – do the illustrations. It was probably an act of kindness that prompted this decision. Collins was certainly an excellent artist, but he was seriously ill (dying of cancer, it turned out). Dickens was happy to see him given a serious project to occupy his time and a source of income. But, after the cover of the new novel was complete, it became evident that Collins was unable to continue. The young artist Samuel Luke Fildes was hired – much to his delight, because this commission established his reputation.

Charles Dickens set his final novel in London and Cloisterham. Cloisterham was based on Rochester – the town in Kent that he grew up in. So in his swan song, Dickens’s story is set in the two places that influenced him the most, the two places that fuelled his creativity. To the landscape of his childhood he brings themes of secrecy and self-division. The last few novels of his career were dominated by the themes of the secret life, of twin identities, of self-division.

|

| The manic John Jasper collapses - illustration from the original issue by Samuel Luke Fildes |

The Mystery of Edwin Drood has been called one of the first detective stories, despite the fact that by the point in the plot where the book ends unfinished, a detective has still not shown up – although the strange character of Mr. Dick Datchery seems to be developing into an investigative figure. He arrives in town out of the blue and shows a particular interest in the characters of our story. The real mystery here is not plot-based, focused on crime and detection; it is the mystery of the secret life of John Jasper, the choirmaster at Cloisterham Cathedral and Edwin Drood’s uncle. As Dickens’s daughter Kate put it, “it is the wonderful observation of character, and his strange insight into the tragic secrets of the human heart.” The gripping portrayal of Jasper – a murderer, perhaps, an opium addict, a thwarted lover – can be seen as a self-revelation of Dickens’s own secret heart: “troubled, with some strong sort of ambition, aspiration, restlessness, dissatisfaction … “

And yet the mystery of Edwin Drood’s fate – clearly telegraphed through several important clues in the book, and revealed directly by Dickens to his close friend John Forster, his illustrator, Luke Fildes, and his son Charley – continued to fascinate readers long after the author’s death. There have been a number of attempts to finish Dickens’s story in print. The first three tries were by Americans: Robert Newell (1870), Henry Morford (1871-1872), and Thomas James (1873). A more recent example has been the book by Leon Garfield (1980). In January 1914, John Jasper – the apparent murderer in Dickens’s book – “stood trial” for the murder of Edwin Drood in London. The “trial” was organised by the Dickens Fellowship. G. K. Chesterton, famed English writer and Dickens enthusiast, served as the judge. George Bernard Shaw was the foreman of the jury, which was made up of other well-known authors. The event was a light-hearted proceeding – Shaw was particularly entertaining, making lots of witty wisecracks. The jury returned a verdict of manslaughter. And Chesterton, “the judge”, ruled that the mystery was insoluble, and then fined everyone present for contempt of court!

|

| 'Princess Puffer' and John Jasper in the opium den - illustration from the original by S. Luke Fildes |

The style of narration in The Mystery of Edwin Drood is more direct and restrained than some of Dickens’s more complex and poetic final novels. It is an easier and simpler read. The chapters focused on the brooding and troubled John Jasper are gripping. But I found the sections dealing with the relationship between Edwin Drood and Rosa Bud quite uninteresting. Likewise the parts dealing with the conflict between Drood and Neville Landless. Reviewers of the book in Dickens’s time seemed to ignore the aspects of the book that were interesting and unique – the exotic theme of opium addiction, for example – and focused on familiar things, like the humour seen in the characters of Durdles, Sapsea, and the Deputy.

While he was writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens suddenly decided to bring some closure to his previous “farewell” tour of public readings – which had been interrupted by his ill-health – by doing a final run of twelve performances. He spread them out so that he would do about two per week. This was new for him – he had never done a series of public readings at the same time as he was working on a novel. He managed to finish this run, but at significant cost to his physical strength. The very last performance in this final series took place on 15 March, 1869 at St. James’s Hall. He did – what else – “A Christmas Carol” and “The Trial from Pickwick”. At the conclusion of the readings he gave a brief farewell speech: “From these garish lights,” he said, “I vanish now for ever more, with a heartfelt, grateful, respectful, and affectionate farewell.” There was a storm of applause and cheering. Dickens’s head was bowed, and there were tears streaming down his cheeks as he left the stage. The thunderous applause would not end. Dickens came back to greet his audience. He raised his hands to his lips in a kiss and then, for the very last time, he was gone.

And then he made what turned out to be his final public speech at the annual dinner of the Royal Academy. “I already begin to feel like the Spanish monk,” he said, “of whom Wilkie [Collins] tells, who had grown to believe that the only realities around him were the pictures which he loved [cheers], and that all the moving life he saw, or ever had seen, was a shadow and a dream [more cheers]."

During the last few days of May, Dickens was working on the sixth instalment of The Mystery of Edwin Drood back at Gad’s Hill Place in Kent. He was in such pain now, with his swollen foot, that he had to take large amounts of laudanum in order to get to sleep. But he still persevered, as ever, with his book. On the morning of 8 June, 1870, he hobbled out from the house, took the tunnel under the main road, and got to work in the study of his Swiss chalet. He was working towards the conclusion of Chapter 23, called “The Dawn Again”. Unusually for him, he came back to work there again in the afternoon. He wrote the final words – “and then falls to with an appetite” – and then broke off for the day, and made his way back to the house an hour before dinner. He spoke briefly to his sister-in-law Georgina, went suddenly pale, and then experienced a fit, and fell to the floor. He never regained consciousness – dying twenty-four hours later on 9 June 1870.

|

| Manuscript - the last page of the last novel |

During the last few days of May, Dickens was working on the sixth instalment of The Mystery of Edwin Drood back at Gad’s Hill Place in Kent. He was in such pain now, with his swollen foot, that he had to take large amounts of laudanum in order to get to sleep. But he still persevered, as ever, with his book. On the morning of 8 June, 1870, he hobbled out from the house, took the tunnel under the main road, and got to work in the study of his Swiss chalet. He was working towards the conclusion of Chapter 23, called “The Dawn Again”. Unusually for him, he came back to work there again in the afternoon. He wrote the final words – “and then falls to with an appetite” – and then broke off for the day, and made his way back to the house an hour before dinner. He spoke briefly to his sister-in-law Georgina, went suddenly pale, and then experienced a fit, and fell to the floor. He never regained consciousness – dying twenty-four hours later on 9 June 1870.

|

| "The Empty Chair" - a tribute to Dickens [showing his desk and chair at Gad's Hill Place] by Samuel Luke Fildes, the illustrator of Edwin Drood [oil on canvas] |

[2012 is the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens. Lots of special events and activities are planned in England this year. Back in 2009, my good friend Tony Grant (in Wimbledon, UK) and I did a pilgrimage to three key Charles Dickens destinations - his birthplace in Portsmouth (the house is a Museum), the house he lived at on Doughty Street in London (now the chief Dickens' museum), and the town he lived in as a child on the north-coast of Kent (Rochester).

These visits inspired me to begin reading through all Dickens's novels. By last summer I had done six, but stalled in the middle of Dombey and Son. I thought what I could do to mark this special year of Dickens was to start again, read through all of his novels inside the year, and blog about them. So this is the seventeenth, and last, of a series.]

[Resources used: "Introduction" to The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Peter Ackroyd (2004); Dickens by Peter Ackroyd (1990)