|

| Dickens in 1837 - a portrait by Samuel Lawrence |

1836 had been an incredibly busy year for Charles Dickens. In February the publisher John Macrone had released a two-volume collection of his Sketches by Boz. A second series was published in one-volume that August. Macrone was also waiting patiently for Dickens to get to work on a promised three-volume novel called “Gabriel Vardon” (which would emerge four years later as the re-titled Barnaby Rudge). By the autumn of 1836, Chapman & Hall had published eight monthly instalments of The Pickwick Papers, but there was still another year to go before its run was complete. Dickens had written a play, The Strange Gentleman, based on one of his sketches; it was running at the St. James Theatre. And he was hard at work writing the libretto for an operetta. In the midst of all of this, Dickens was approached by a third publisher, Richard Bentley, with a proposal to edit a new monthly magazine, to be called Bentley’s Miscellany. Amazingly, the overstretched author agreed to take on yet another project - not just writing, but editing a magazine. He considered himself now truly committed to a literary career, and ready - finally - to give up his post as journalist at The Morning Chronicle.

In addition to editing the work of the other contributors to the magazine, Dickens would also write a piece of fiction for each instalment. And he would get pride of place, of course – the first piece in each issue. For the first edition of Bentley’s Miscellany - published in January 1837 - Dickens could only manage a farcical tale in the style of his Boz sketches. But then in mid-January, he informed Bentley that he’d hit upon a great idea for a novel. It would be a polemical story aimed at satirising the worst effects of the New Poor Law – a series of measures which had been introduced back in 1834, but whose social repercussions were only now starting to reveal themselves. In the planned novel, Oliver Twist, Dickens proposed to portray the harsh results of the new law by focusing on the life of an infant born in a parochial workhouse.

The first two chapters of Oliver Twist appeared in Bentley’s Miscellany in February 1837, accompanied by George Cruikshank’s steel etching showing “Oliver asking for more”. Dickens had trouble, at first, with the new format. The first instalment was too short. But he soon had the work under control. The problem was that for the first time ever a major novelist was writing and publishing two different novels simultaneously in monthly instalments. And the two novels were not only of a very different style and theme, they were also written to different lengths. By February 1838, The Pickwick Papers was into its twelfth issue (Chapters 32-33). There were seven instalments to come. So, for seven months, Dickens would begin the month writing two chapters of Oliver Twist in 9,000 words; and then switch to an instalment of The Pickwick Papers which was twice as long - 19,000 words. He would write up to the last week of the month, when both novels would be quickly published in the last few days of the month. He would start the month deep in lurid melodrama, and finish with the satiric good-humour of picaresque adventure. And he managed to juggle these opposite assignments with ease. Ideas poured out of him: incidents, characters, and plot-lines. He was digging deep into his imagination.

But suddenly he was thrown off course. On May 7, Mary Hogarth, his wife Catherine’s younger sister, who was living with the family in their new home on Doughty Street, suddenly took ill one evening after they had returned from the theatre. Mary's condition declined rapidly overnight, and she died in Dickens’ arms the next day. He was devastated. She had assumed a special importance in his life. He was thrown into an extended period of grief – revealing later that he dreamed about her every night for nine months! After the funeral, he and Catherine took a two-week country retreat in Hampstead. And, for the first and only time in his writing life - a 34-year career of fourteen novels written in monthly instalments - he missed a deadline. In June there was no new issue for either The Pickwick Papers or Oliver Twist. He was back into the swing of things in July, taking up again the story of Fagin and his gang (Chapter 9); but the tone and focus of Oliver Twist would change significantly.

Oliver Twist is likely the first novel in English which features a child as its central character. In doing this, Dickens was combining the roles of novelist and journalist. There had been recent news of an inquiry into the deaths of workhouse children, who had been “farmed out” into the care of women in private homes. Dickens presents Oliver as representative of these workhouse orphans. Oliver, too, is farmed out, and the treatment he receives from his guardian, Mrs. Mann, is not much better than that he had suffered at the workhouse. The first section of the novel (seven brief, but vivid, chapters) depicts the oppressive treatment Oliver suffers at a parochial workhouse. Dickens writes here with brutal realism, but the polemics are made more effective through the use of dramatic exaggeration and an often savage sarcasm. Unlike many of his books, which tend toward the prolix, this one moves along briskly. After famously asking for more food - not just for himself, but also for his fellow starving inmates - he is “sold” to the local undertaker. Again he suffers abuse. He runs away, and walks all the way to London. Arriving in the capital, exhausted and hungry, he is taken in hand by Jack Dawkins, the Artful Dodger, who brings him back to the squalid lair of Fagin, “the Respectable Old Gentleman” – who trains and controls a small team of children working as pickpockets in the London streets.

The opening chapters, focused on the workhouse, have Oliver serving as a tool for Dickens’ polemic. But once the scene shifts to the London underworld, Dickens’ imagination starts to invest the story of his title-character with elements of his own childhood experience. Throughout the novel, Oliver is a passive pawn in the hands of fate. In the workhouse, he merely suffers abuse and neglect. But in the hands of Fagin, he is in a much more dangerous situation. It is not just the threat to his physical survival that faces him now; it is the danger of social and moral degradation. There were perhaps only a very few people in Dickens’ immediate circle who knew how Dickens was drawing on his own childhood experience. When his father was consigned to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison - his mother and siblings would later join his father - Charles was sent to work at the Warren’s Blacking Warehouse. Dickens was left to fend for himself and he found the whole situation a great humiliation. There was a friendly young man at Warren’s, named Bob Fagin, who took Charles under his wing. But Dickens came to see this intervention as a kind of threat – in some sense, he thought Bob was encouraging him to accept his social degradation. And the figure of Fagin in Oliver Twist represents that same danger – he tries to entice Oliver to accept the twisted morals of this criminal gang. He attempts to seduce the boy into accepting life as a thief. Some of the author’s deepest anxieties are reflected in Oliver’s struggle to survive. His protagonist is portrayed as a boy with a deep instinct for human goodness and feeling. It always serves to protect him from the abuse of the uncaring and the machinations of the wicked.

|

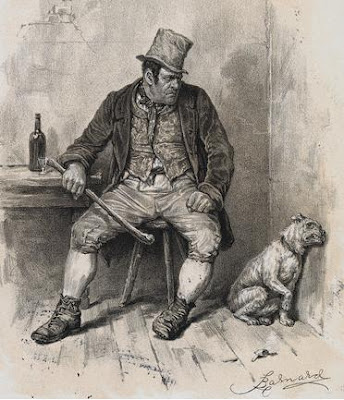

| Bill Sikes and his dog, Bulls Eye |

And with the sudden death of Mary Hogarth, and the grief that followed, the focus of the book shifts again; it becomes less satirical and more personal. Once Oliver has been rescued from the clutches of Bill Sikes by the Maylie family, his story is pretty much complete. What Dickens gives us now is a kind of parable about the triumph of good over evil; innocence is vindicated in its struggle against moral corruption. Dickens seems to lose interest in the topical and polemical elements of the early section, and focuses instead on the domestic themes of home, childhood and early death. The character of Rose Maylie is introduced as an idealised portrait of the deceased Mary Hogarth - but in this fictional world of wish-fulfilment she survives a serious illness that brings her to the brink of death. And Dickens constructs a complicated - and rather tedious - mystery about the true identity of Oliver’s mother and her family. The concern here is to establish the fact that Oliver deserves his happy fate, because he is not really a waif; he is the child of middle-class parentage.

Many contemporary critics of the book missed this social conservatism; they were shocked by the lurid depiction of the London underworld. By the 1840s, Dickens’ book was lumped in with the so-called “Newgate novels”, which included William Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard and Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford and Eugene Aram. These books were condemned. They were accused of depraving and corrupting their readers by glamorizing the lives of thieves and prostitutes. Dickens was indignant with this sort of criticism – especially the fierce attack of William Thackeray who ridiculed the genre in general, but Oliver Twist specifically. As Dickens points out, though, his criminal characters are not glamorized: Bill Sikes is an unrepentant thug, with no redeeming features; Fagin is sympathetic only in the gross exaggeration of his comic depiction; and Nancy regrets her life of crime, and takes action to save the innocent Oliver. Nonetheless, Dickens did revel to some extent in the melodramatic excess of some of this sordid detail. Famously, in later life, he would give public readings from his novels; and the description of Bill Sikes’ murder of Nancy was one of his favourite choices. It always left the audience emotionally drained, and Dickens physically exhausted.

|

| Fagin awaits execution in Newgate Prison |

The depiction of Fagin in Oliver Twist, unfortunately, is tainted by its anti-semitism – typical of its period. Not only does Dickens describe Fagin physically as a repulsive human being – almost bestial, but he refers over and over to this character as “the Jew”. It’s well known, of course, that the prejudice of the time denied Jews access to many areas of social and business life. Those Jewish entrepreneurs interested in business and money were excluded from most elements of finance, and were reduced to the role of money-lender, pawnbroker and usurer – or criminal activities like theft and the fencing of stolen property. The latter activities, of course, were Fagin’s modus operandi. Dickens spares no chance in depicting him as a loathsome individual. Eliza Davis wrote to Dickens to criticise his portrayal of Fagin. She argued that he "encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew" - and that had done a great wrong to the Jewish people. At first Dickens reacted defensively to her letter, but he then halted a later edition of Oliver Twist, and changed the text for the parts of the book that had not yet been set - which is why Fagin is called "the Jew" 257 times in the first 38 chapters, but barely at all in the next 179 references to him – where he’s called simply Fagin.

Oliver Twist is one of Dickens’ most popular novels. Because it was published monthly in Bentley’s Miscellany, a magazine that featured a host of other contributors, he adopted the melodramatic, adventurous style typical of those sorts of compendia. Readers respond instinctively to the plight of the innocent young orphan struggling against a host of hypocritical, cruel adults – depicted with trenchant sarcasm and sly humour. It’s also one of his shortest novels – a plus for those daunted by the 800-page length of most of his discursive epics. And the characters of Oliver (the boy who dared ask for more), Mr. Bumble (the parochial beadle who uttered the immortal line: “If the law supposes that, then the law is a ass, a idiot!”), Fagin, Bill Sikes and Nancy have become some of the most-widely recognized fictional characters in the English language. Despite the didactic intention of the novel, Oliver Twist is a surprisingly poetic work. Dickens’ response to the traumatic death of Mary Hogarth gives much of the second-half of the book a dreamlike intensity: full of mystery, visions, and romance. Oliver emerges unscathed from the almost metaphysical struggle between Fagin’s world of seductive wickedness and the secure goodness found in the world of the Maylies and Mr. Brownlow. And if you don’t find it a most captivating read, I’ll eat my head.

[2012 is the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens. Lots of special events and activities are planned in England this year. Back in 2009, my good friend Tony Grant (in Wimbledon, UK) and I did a pilgrimage to three key Charles Dickens destinations - his birthplace in Portsmouth (the house is a Museum), the house he lived at on Doughty Street in London (now the chief Dickens' museum), and the town he lived in as a child on the north-coast of Kent (Rochester).

These visits inspired me to begin reading through all Dickens's novels. By last summer I had done six, but stalled in the middle of Dombey and Son. I thought what I could do to mark this special year of Charles Dickens was to start again, read through all 14 of his novels inside the year, and blog about them. I'll give it a try, anyway! So this is the third of a series.]

Next - Nicholas Nickleby

|

| Mr. Bumble, the Beadle: "The law is a ass, a idiot". |

[2012 is the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens. Lots of special events and activities are planned in England this year. Back in 2009, my good friend Tony Grant (in Wimbledon, UK) and I did a pilgrimage to three key Charles Dickens destinations - his birthplace in Portsmouth (the house is a Museum), the house he lived at on Doughty Street in London (now the chief Dickens' museum), and the town he lived in as a child on the north-coast of Kent (Rochester).

These visits inspired me to begin reading through all Dickens's novels. By last summer I had done six, but stalled in the middle of Dombey and Son. I thought what I could do to mark this special year of Charles Dickens was to start again, read through all 14 of his novels inside the year, and blog about them. I'll give it a try, anyway! So this is the third of a series.]

Next - Nicholas Nickleby