| |

| A woodcut engraving of Dickens in 1838 |

Charles Dickens still had about a dozen monthly instalments left to write of Oliver Twist when he began work on Nicholas Nickleby in February, 1838. He was twenty-five years old and riding the crest of a wave. This new book - his fourth - would be his third novel. It proved to be hugely successful and confirmed his status as the most popular novelist of his generation. The first issue of his Pickwick Papers, published two years previously, had consisted of just 400 copies. Nicholas Nickleby sold almost 50,000 copies on the very first day of its publication (April 1st., 1838).

Dickens had signed a contract with his publisher, Chapman & Hall, to write the new novel back in November, 1837 – so it took him several months to decide on a subject, a theme and a style for the new work. His general idea was to combine the best elements of Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, but also to add something new. He wanted some of the humour and picaresque adventure found in Pickwick Papers; but he also intended to provide more of the hard-hitting social satire he’d used in Oliver Twist. His vision extended even further than that - he planned to focus these disparate elements around a plotline that would become essentially his first romance. The novel would tell the story of young Nicholas Nickleby, an aspiring young gentleman, much like himself, struggling against the vicissitudes of the world.

|

| Cover wrapper for the new novel |

Like most of his novels, Nicholas Nickleby was written in 20 monthly instalments. Each issue consisted of 32 pages of text and two illustrations done by Hablot Browne (“Phiz”). They cost one shilling. The first issue was published in March 1838; the final instalment (a double-issue priced at two shillings) came out in September, 1839. So, like the ten-month period in 1837, when Dickens was writing both an instalment of Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist each month, from April 1838 to April 1839 Dickens was writing Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby simultaneously. He seemed to thrive on the pressure of meeting constant deadlines.

The initial idea that fired up Dickens’s imagination was to write a polemical satire - in fictional form - of the so-called “Yorkshire schools”. Following the success of Oliver Twist in bringing the issue of child abuse in parish workhouses to the general public’s attention, Dickens decided to court public opinion again – this time in regard to certain disreputable boarding schools in Yorkshire which were used as dumping grounds for illegitimate and unwanted children. Really, these schools were little more than juvenile prisons. The children were abandoned to horrible situations – suffering near-starvation diets and deplorable health conditions. Dickens had heard and read about these establishments in his childhood and they had been in the news again recently. He decided to investigate. He took his illustrator, Hablot Browne, up North with him and visited the Bowes Academy in Greta Bridge – near Barnard Castle in West Yorkshire. The place was run by a certain William Shaw. His apparent cruelty became the model for the vicious and dishonest Wackford Squeers – the entrepreneurial headmaster of the fictional Dotheboys Hall. Dickens succeeded in his plan; thanks to the lurid description of Dotheboys Hall in his new book, the twenty-or-so Yorkshire boarding schools were gone within a generation, victims of an outraged public.

|

| The "internal economy" of Dotheboys Hall: brimstone and treacle served by Mrs. Squeers |

A new element in Dickens’s technique in this new book was to create characters with physical deformities – used to embody their moral depravity and then exaggerated for comic effect. These characterizations often tend towards the grotesque, but Dickens is not essentially providing realistic portraits; the characters’ deformities are worn much like a mask – they represent an attitude, or a state of mind. The one-eyed Wackford Squeers, for example, is blind to his own wickedness. His obnoxious son is obese – and busy tormenting the half-starved waifs in his father’s “school”. But it’s not just the evil characters that are physically deformed – some of the good ones are too: Smike, the pathetic youth who has been oppressed by Squeers for many years in Dotheboys Hall, is lame and half-witted. Newman Noggs, Ralph Nickleby’s servant/assistant, is a bundle of deformities. The physical weaknesses here serve as a sharp contrast to their inner benevolence – emphasizing the cruelty they have suffered.

Nicholas Nickleby is an uneasy blend of satire, picaresque comedy, romance and melodrama. As such, Dickens continues to exploit techniques and situations that had proved successful in his previous books. And the public seemed to love these epic stories in which Dickens mixes genres and alternates styles. After the early polemic against the Yorkshire schools, Dickens puts Nicholas on the road to Portsmouth, where he encounters a travelling acting-troupe under the jovial leadership of Vincent Crummles. This long episode, in which the young Nickleby takes on the role of playwright and leading-actor [Dickens had toyed with the idea of the theatre as a vocation], is a comic interlude in a story that is primarily a romantic melodrama. The romance involves Nicholas’s struggle to vindicate his self-image as a young gentleman in search of love, career prospects, and a fortune. He works to save his “princess” (the lovely Madeline Bray) from a forced marriage to a despicable old money-lender. Nicholas also struggles against the wicked machinations of his main antagonist - his depraved uncle, Ralph Nickleby. His uncle works throughout the novel to thwart his nephew's plans and to ruin the lives of his widowed sister-in-law and her two children, Nicholas and Kate.

|

| Fanny Squeers tries to interest Nicholas |

It’s the character of Ralph Nickleby that keeps the book alive, because mid-way through the book, Nicholas comes under the paternal care of the unbelievably benevolent Cheeryble brothers, who run a successful business in the city of London and shower love and largesse on whomever catches their fancy. There is no more financial struggle for Nicholas and, like Oliver Twist before it (where Oliver lands safe, mid-novel, in the bosom of the Maylie family), the plot falters and the book goes soft. In another similarity with the previous book - which stretched out a convoluted plot-line to explain the mystery of Oliver’s parentage - this novel also creates a mystery about the secret parentage of Smike, and the people who abandoned the child to the cruel care of the Squeers family.

In a melodrama there is scant little character development - things happen, coincidences occur. And the author gets busy announcing what has happened, telling us what the characters think and feel, and moving his heroes and villains through each plot-point, and on to the inevitable conclusion, with young couples pairing up and ensconcing themselves safely in their comfy homes at the happy conclusion.

What saves Nicholas Nickleby from being mere melodrama - as usual with Dickens - are some interesting and delightful characters. There is the foppish Mr. Mantalini, who is forever disappointing his practical and business-minded wife and blustering his way along with a stream of vapid endearments and alibis. There is the put-upon man-servant Newman Noggs, who seems weak and pathetic, but always turns up at key moments to save the day and thwart his evil employer. There is the vile Sir Mulberry Hawk, who engages in a long campaign of attempting to seduce Nicholas’s sister Kate - assisted by their uncle Ralph. And there is Ralph, himself – a relentlessly malevolent figure devoted to the pursuit of money and the exploitation of everyone within his sphere of influence. In some ways, the driving ambition of this character reveals unwittingly, perhaps, the inner disposition of his author – who wants us to identify him with the ardent and sensitive young Nicholas struggling to make his way in a corrupt world. But there is a lot of the relentless ambition and need for financial security in Ralph Nickleby’s character to be found in the secret world of Dickens’s troubled heart.

And, then, there is Mrs. Nickleby, Nicholas’s and Kate’s mother. She is a feckless woman and, at every key moment, comes to the wrong conclusion and makes a poor judgment about people. It is thought that there is a lot of Elizabeth Dickens, Charles Dickens’ mother, in this portrait of Mrs. Nickleby. She annoys us with her lack of insight and her gullibility at the hands of scoundrels. And she is forever rambling on about some memory from the past – and gets lost in a strange and tortuous string of associations, in which she always forgets what she is supposed to be remembering. But some of these long, rambling speeches of hers are droll and diverting – early examples, really, of stream-of-consciousness-thinking put into monologue form.

In its day Nicholas Nickleby was immensely popular and consolidated Dickens’s hold on the public’s imagination and heart. If the book strikes us today as rather unshapely and overly-melodramatic, it still manages to compel us with its vigorous description, grotesque and comic characters, funny set-pieces, and drawn-out story-lines. And despite the transparencies seen in some of his techniques and stylistic flourishes, Dickens still draws you in, and leads you on, with the sheer exuberance of his imaginative power. But what is it that stays with you, once the book is back on the shelf? For me, it's those early chapters set in the Yorkshire school at Dotheboys Hall: Nicholas thrashing Wackford Squeers with his own cane and taking poor Smike to safety. He might veer too often towards pathos and sentiment, but Dickens truly knew how to touch the human heart and stir his readers’ sense of compassion.

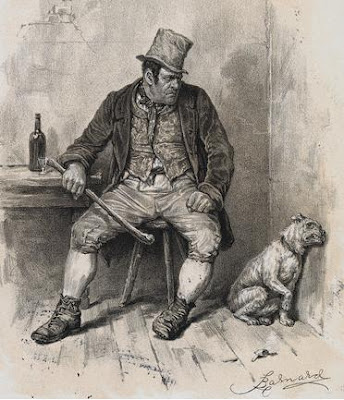

|

| Nicholas thrashes Squeers with his own school cane |

[2012 is the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens. Lots of special events and activities are planned in England this year. Back in 2009, my good friend Tony Grant (in Wimbledon, UK) and I did a pilgrimage to three key Charles Dickens destinations - his birthplace in Portsmouth (the house is a Museum), the house he lived at on Doughty Street in London (now the chief Dickens' museum), and the town he lived in as a child on the north-coast of Kent (Rochester).

These visits inspired me to begin reading through all Dickens's novels. By last summer I had done six, but stalled in the middle of Dombey and Son. I thought what I could do to mark this special year of Charles Dickens was to start again, read through all 14 of his novels inside the year, and blog about them. I'll give it a try, anyway! So this is the fourth of a series.]

Next: The Old Curiosity Shop

[Resources used: "Introduction" to Nicholas Nickleby by John Carey (1993); Dickens by Peter Ackroyd (1990) ]